NIR BARZILAI HAS a plan. It’s a really big plan that might one day change medicine and health care as we know it. Its promise: extending our years of healthy, disease-free living by decades.

And Barzilai knows about the science of aging. He is, after all, the director of the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx. And, as such, he usually talks about his plan with the caution of a seasoned researcher. Usually. Truth is, Barzilai is known among his colleagues for his excitability—one author sayshe could pass as the older brother of Austin Powers—and sometimes he can’t help himself. Like the time he referred to his plan—which, among other things, would demonstrate that human aging can be slowed with a cheap pill—as “history-making.” In 2015, he stood outside of the offices of the Food and Drug Administration, flanked by a number of distinguished researchers on aging, and likened the plan to a journey to “the promised land.”

Last spring, Barzilai traveled to the Vatican to discuss the plan at a conference on cellular therapies. It was the second time he’d been invited to the conference, which is a pretty big deal in the medical world. At the last one, in 2013, he appeared alongside a dwarf from Ecuador, a member of a community of dwarfs whose near immunity to diabetes and cancer has attracted the keen interest of researchers. The 2016 conference featured a number of the world’s top cancer scientists and included addresses from Pope Francis and Joe Biden. That Barzilai was invited was a sign not only of his prominence in his field but also of how far aging research, once relegated to the periphery of mainstream science, has come in recent years.

That progress has been spurred by huge investments from Silicon Valley titans, including Google’s Sergey Brin and Larry Page, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, PayPal cofounder Peter Thiel, and Oracle cofounder Larry Ellison. Armed with such riches, biotech researchers are now dreaming up a growing list of cribbed-from-science-fiction therapies to beat back death: growing new organs from your own DNA, infusing older bodies with blood and stem cells from young bodies, uploading brains to computers.

Almost nothing seems too far-fetched in the so-called life-extension community. And yet, while it’s certainly possible that this work will lead to a breakthrough that will benefit all of humanity, it’s hard to escape the sense that Silicon Valley’s newfound urge to postpone aging indefinitely is, first and foremost, an attempt by the super wealthy to extend their own lives. As one scientist recently put it to The New Yorker, the antiaging science being done at Google-backed Calico Labs is “as self-serving as the Medici building a Renaissance chapel in Italy, but with a little extra Silicon Valley narcissism thrown in.”

Barzilai’s big plan isn’t necessarily less quixotic than those being dreamed up at Silicon Valley biotechs. It’s just quixotic in a completely different way. Rather than trying to develop a wildly expensive, highly speculative therapy that will likely only benefit the billionaire-demigod set, Barzilai wants to convince the FDA to put its seal of approval on an antiaging drug for the rest of us: A cheap, generic, demonstrably safe pharmaceutical that has already shown, in a host of preliminary studies, that it may be able to help stave off many of the worst parts of growing old. Not only that, it would also shorten the duration of those awful parts. (“How To Die Young at a Very Old Age” was the title of his 2014 talk at TEDx Gramercy in New York City.)

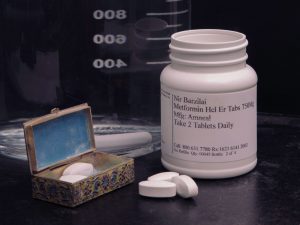

The drug in question, metformin, costs about five cents a pill. It’s a slightly modified version of a compound that was discovered in a plant, Galega officinalis. The plant, also known as French lilac and goat’s rue, is hardly the stuff of cutting-edge science. Physicians have been prescribing it as an herbal remedy for centuries. In 1640, the great English herbalist John Parkinson wrote about goat’s rue in his life’s work, Theatrum Botanicum, recommending it for “the bitings or stings of any venomous creature,” “the plague,” “measells,” “small pocks,” and “wormes in children,” among other conditions.

According to some sources, goat’s rue was also a centuries-old remedy for frequent urination, now known to be a telltale sign of diabetes. Today, metformin, which helps keep blood sugar levels in check without serious side effects, is typically the first-choice treatment for type 2 diabetics, and it’s sometimes prescribed for prediabetes as well. Together, the two conditions afflict half of American adults. In 2014 alone, Americans filled 76.9 million prescriptions for metformin, and some of those prescriptions went to Barzilai himself. (He’s been taking the drug since he was diagnosed with prediabetes around six years ago.)

A native Israeli, Barzilai speaks English with an accent, never letting grammatical slipups slow him down. He has short, boyish bangs and a slightly rounded face. His thick glasses and natural exuberance give him the look of an actor typecast as an eccentric researcher. He traces his interest in aging to the Sabbath walks he took with his grandfather as a child. Barzilai could never quite reconcile the frailty of the old man with his grandfather’s stories of draining swamps in prestate Israel. “I was looking and saying, ‘This guy? This old guy could do that?’”

Barzilai first studied metformin in the late 1980s while doing a fellowship at Yale, never imagining the drug would later become his focus. When the FDA approved it as a diabetes treatment in 1994, there was little reason to think it would someday become one of the hottest topics in medicine. But in the following two decades, researchers started comparing the health of diabetics on metformin to those taking other diabetes drugs.

What they discovered was striking: The metformin-takers tended to be healthier in all sorts of ways. They lived longer and had fewer cardiovascular events, and in at least some studies they were less likely to suffer from dementia and Alzheimer’s. Most surprising of all, they seemed to get cancer far less frequently—as much as 25 to 40 percent less than diabetics taking two other popular medications. When they did get cancer, they tended to outlive diabetics with cancer who were taking other medications.

As Lewis Cantley, the director of the Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine, once put it, “Metformin may have already saved more people from cancer deaths than any drug in history.” Nobel laureate James Watson (of DNA-structure fame), who takes metformin off-label for cancer prevention, once suggested that the drug appeared to be “our only real clue into the business” of fighting the disease.

The more researchers learn about metformin, the more it can seem like a medieval wonder drug poised for a 21st century resurgence. In addition to exploring its potential to help treat the most common afflictions of aging, researchers are now also investigating whether metformin might improve symptoms of autoimmune disorders, tuberculosis, and erectile dysfunction, among other conditions. And while much of this research is still in its early stages and may fizzle, metformin is already prescribed off-label to treat obesity, polycystic ovarian syndrome, infertility, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and acne—not bad for a plant that the USDA officially lists as a noxious weed.

Barzilai, like most in his field, was aware of the good news about metformin that had been trickling out year after year. But the true origins of his big plan have less to do with metformin itself than with a convergence of a number of different strands of aging research. The first breakthroughs came in the ’90s, when researchers demonstrated that a single mutation in a microscopic worm could double its lifespan. Among the takeaways: The aging process might not be as hopelessly complex as it had previously seemed. As this new understanding of aging was settling in, Barzilai was beginning a series of studies on people who live to unusually old ages—“superagers,” as Barzilai calls them.

In the course of that work, he began to notice a pattern that other researchers had also seen: The superagers died from the same diseases as everyone else, but they developed them years later and, critically, closer to the ends of their lives. In other words, if you could slow the aging process, you might do more than give someone a few more years. You could also be able to shrink the suffering and enormous expense that accompanies cancer, heart disease, dementia, and all the other plagues of growing old.

The true promise of antiaging drugs, Barzilai and his colleagues came to think, wasn’t immortality. The ideal drug might not even extend life for all that long. Instead, it would extend what Barzilai and his colleagues call our health span—the years of healthy, disease-free living before the diseases of aging set in. S. Jay Olshansky, a professor at the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois at Chicago, is advising a small team of researchers who are working with Barzilai on a new study of metformin’s antiaging properties. He believes that even a modest slowing of the aging process—and the subsequent extension of health span—would have a greater impact on health and quality of life than a cure for cancer. The upshot: a multitrillion-dollar economic benefit in the decades ahead.

In 2013, Barzilai and two other researchers received a small grant from the National Institute on Aging to explore how the field might move forward. That grant, in turn, led to a 2014 conference in the Spanish countryside, where several dozen researchers gathered in a medieval castle turned hotel to map out a path forward. The castle, surrounded by ancient stone walls and towers, was the sort of place where goat’s rue may have once been handed out by local herbalists. Barzilai describes it as a “Spanish prison.” But the isolation of the setting turned out to be a good thing. “We were stuck in this place with one another,” says Steven Austad, a researcher at the University of Alabama. “It was really quite intense.”

The assembled scientists and academics focused on one obstacle above all: the Food and Drug Administration. The agency does not recognize aging as a medical condition, meaning a drug cannot be approved to treat it. And even if the FDA were to acknowledge that aging is a condition worthy of targeting, there would still be the question of how to demonstrate that aging had, in fact, been slowed—a particularly difficult question considering that there are no universally agreed-on markers. What they needed, Barzilai and the others concluded, was a precedent-setting test case—a single study that would change the rules forever, not unlike how trial lawyers search for a perfect plaintiff when they’re going to the Supreme Court to set a new legal precedent.

Which drug to use for this precedent-setting case was less obvious. Austad was among those who favored a drug called rapamycin, which has been shown to outperform metformin in studies of longevity in animals. But Barzilai was concerned about rapamycin’s powerful side effects. (An immunosuppressant, it raises the risk of opportunistic infections.) “One thing I don’t want to do is to kill anyone,” Barzilai tells me.